BALTA

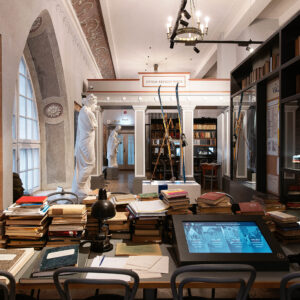

Ping-pong-ping-pong sounds the ball, flying back and forth across the table. A quiet backyard area untouched by the wind permits the game to become faster and faster. Part of the audience is preoccupied with the game, others are deeply engaged in conversation. More and more guests arrive. A metallic screeching sound accompanies somebody opening the gate from the side of the street; people enter knowingly into the little hidden yard, skilfully push the gate shut, and either join the buzzing conversation or walk directly towards the indoor space. Behind a double-sided iron door with flags of the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic and the United States draped side-by-side, covering its windows, are comfy caféarmchairs, sofas, coffee tables, a bar, a freezer, locals and guests enjoying life. A basketball hoop has been installed in the backroom, a TV, a piano, a soft couch, a boxing bag. Different shelves, construction materials, cans of paint and other items, uncategorised; arranged without explanation. A great old linden tree growing in the dim corner of the room makes its way through the roof. In the adjacent room, metal frames for silk screen printing, pots, papers, notebooks, a printer, extension cables, aerosol spray paint, sound mixers, loudspeakers, acrylic paintings, posters, a large board with organisational notes written on it, pillows, hangers, T-shirts, digital and analogue technical bits all catch the eye.

Balta is a hybrid of a silk screen printshop and a bar for close friends. Its spatial use and construction logic is closely tied to its founders and changing needs: it is a place whose structure is a co-creation of the entire community. To best describe the project architecturally, it is reasonable to regard the establishment as a flow; an accumulation and recycling of materials. Such a dispersion of authorship and, above all, a material-based point of view is rather a matter of spatial aesthetics, one that provides a visible, perceptible experience of sensuosness and physicality. How is a community bound to its space? 1 This question is central to one of the founders of Balta whose diploma thesis at the Estonian Academy of Arts this year was a research paper on the formation of the establishment. That question, along with some others, is also at the core of the given essay.

COMMUNITY

Located in the middle of the whirls of gentrification in the Balti Jaam railway station and Kalamaja district in Tallinn, where capitalist undercurrents seek unprecedented experiences to profit from, Balta is a site both as a place and a building. The construction and planning phase in a traditional free market economy business model is short to keep loss of rent profits minimal. The purpose of short deadlines is to finish the building and open to the public quickly. A grand opening ensues; an employee is hired to tend to the guests, as expected. The quality of construction and interior design are important factors that create the mood that provokes guests to spend, to a larger or lesser degree.

Balta was set up in a former bottle return centre that had originally operated as a silk screen print studio and gradually expanded into a shared space for work and leisure. It was originally founded as a community without a work schedule, delivery chain, coercion or personal gain.2 Although by now there is a bar that accepts the euro, the original free spirit and mood remain, appreciated clearly by all the founders and guests.

It would seem pertinent to consider the term “community“ for a moment. One of the focal ideas of a community is the blurred line between private and public space. It is held together, not by kinship ties, but by a group that voluntarily share, organise and sustain a space amongst themselves, changing it when necessary in accordance with their needs and interests. Throughout history there have been attempts at architectural projects tightly bound with space and the communal way of life. In the 19th century, Charles Fourier tried to physically centralise so-called phalansteries, or self-sufficient dwelling and production units, under one roof. A phalanstère blurred the lines between a public sidewalk, a private living room, a collective work space and even the traditional man-woman marital relationship. The excessively idealistic ideas of Fourier were too definitive and radical at the time to have found support.

A century later, a similar idea of living, working and spending free time conjointly was adopted by the revolutionary Soviet Union, where architect Moisei Ginzburg led the construction of one of the most avant-garde buildings of the 20th century – the Narkomfin apartment building in Moscow with shared kitchens, washrooms, children’s daycare and gardens, fine-tuned by a library and a gym. Despite the fact that such a utopian edifice was actually completed, it did not become the utilitarian centre it had been devised to be.

/…/