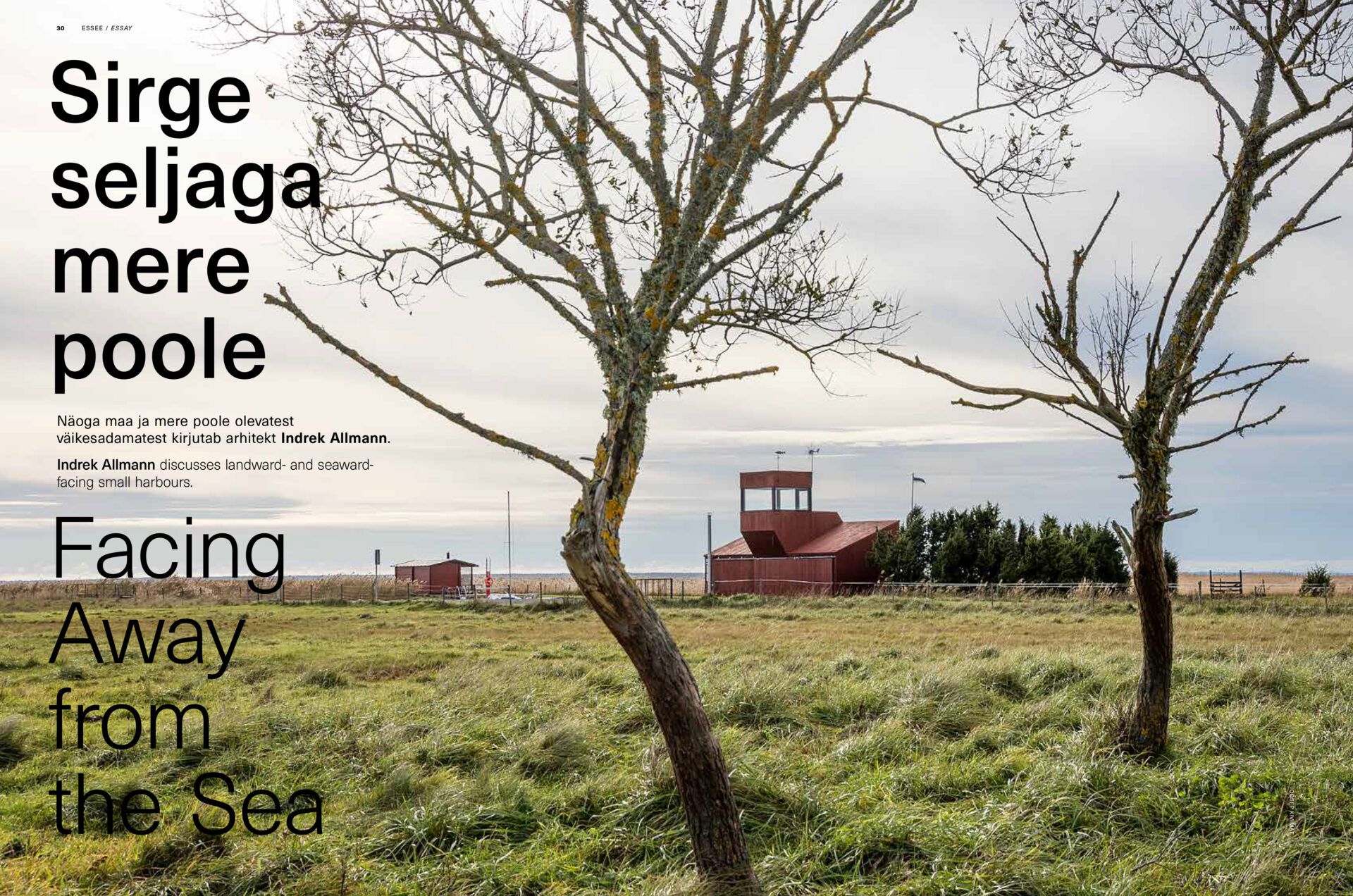

Indrek Allmann discusses landward- and seaward-facing small harbours.

All islands have one fundamental thing in common: they are surrounded by water. This water might be exploited for recreation as well as fishing, but above all, it is a space for mobility. For as pleasant as it may be to stay on an island, at some point you are going to have to leave. Islands are connected by waterways, which are really nothing but maritime siblings of land roads. They differ simply in their environment and the means of transport used. Smart use of waterways enables islanders to perceive the spatiotemporal component of mobility space in a very different way than those who move only on dry land. Thus, in fair weather, the islanders of Hiiumaa can reach Sweden by a motorboat in about two hours (84 nmi from Kalana to Svenska Högarna), almost in the same time as Tallinn (74 nmi from Heltermaa to Vanasadam), whereas Finland can be reached in only about an hour (50 nmi from Kärdla to Hanko eastern harbour) and Kihnu in about the same (57 nmi from Heltermaa to Kihnu). When the weather is rough, however, everything is different and travelling the same routes could take days.

While 15 years ago, there were around 16,000 recreational craft in Estonia, the number of registered craft has now risen to 34,000. There has been a constant increase by 1,200 craft in a year. Also, the size of the craft has changed. While most boats used to be of the 4.5–5.5 metre class, the average craft today is significantly seaworthier—at least 7.5 m long. At the same time, the increase in the number of berths has been ten times slower, which has led to a deficit and severely hampers further maritime development. Due to the lack of mooring places, many have no other option than to keep their boat on a trailer in their backyard. This in turn means that to move the boat, they need to have a larger sort of SUV. According to the Association of Estonian Marine Industries and Small Harbour Competence Centre, there are altogether 3500 berths in Estonian harbours. Granted, there are also unregistered domestic jetties, but the number is still ten times lower than the number of boats. Compared to Finland and Sweden, these figures are extremely small. For example, the harbour of Bullandö alone, which serves as a connection with the surrounding islands, has more than 1400 places for watercraft.

Just like there are different people, there are also different harbours. The most important point of difference lies in whether the harbour has been designed to face towards land or face towards the sea. Landward-facing ones tend to include all the ferry ports, the purpose of which is merely to get the passengers quickly and efficiently on the ferry and take them to a similar destination, where they are quickly driven out again. There can also be landward-facing small harbours, whose restaurant and sunset-lit pier or viewing platform are visited in the same manner you would visit, say, the foyer of a modern opera building, and without any desire to head out to the sea. A landward-facing small harbour looks nice and occasionally romantic when approached from the land, but its fairway contains more sand than water.

A seaward-facing harbour strives to have a strong influence on the planning on land. In such a harbour, wind turbines or roof ridges form a leading line demarcating waterway, and upon entering the harbour basin, you can immediately figure out which berths are meant for visiting vessels, which berths are there for the residing ones, and where a boat that has suffered an accident could moor and get out of water. The restaurant in a seaward-facing harbour is placed in a way that enables a visiting yacht owner to see the swaying mast of their sailboat; there is no need to rent a bicycle to get to the toilet or washing room; the sauna is placed so that you can go swimming from there; there are picnic shelters and fully equipped barbecuing spots near the visitors’ berths, and one does not have to go through code-locked gates while carrying heavy supplies or repair equipment to get to one’s boat, because the plan of the harbour itself discourages ignorant landlubbers from hanging around the floating docks. Granted, there are also some examples that go over the top—harbours where the docks and the nearest building are separated not by cosy picnic tables and an outdoor gym, but rather by a huge asphalt lot, because, well, maybe some historical sailboat will someday happen to drop by and want to dry its large sails there, and also, it is nice to have all the sailboats lined up there for the winter, instead of having to drive them around the corner. Such overeagerly seaward-facing harbours are actually faced towards ‘shore admirals’, I suppose.

/…/

Full article: https://ajakirimaja.ee/en/facing-away-from-the-sea/