Humankind is transforming the planet into a vast infrastructural project serving its economic system. Landscape architect Hannes Aava explores how this development is reflected in critical theory and discusses what must be done to prevent the metabolism of humankind from becoming a metastasis.

News reports of cables and pipelines damaged or destroyed by explosions or ship anchors in the depths of the Baltic Sea, a 500 MW energy battery planned 750 metres underneath the limestone cliff in Paldiski, rapidly expanding solar parks, ports, and airports, and the public’s excitement over the opening of new dual carriageways all illustrate that infrastructure and the natural environment it occupies are not only in the spotlight and politically charged but also fundamentally define humanity’s relationship with the environment.

Technical landscapes

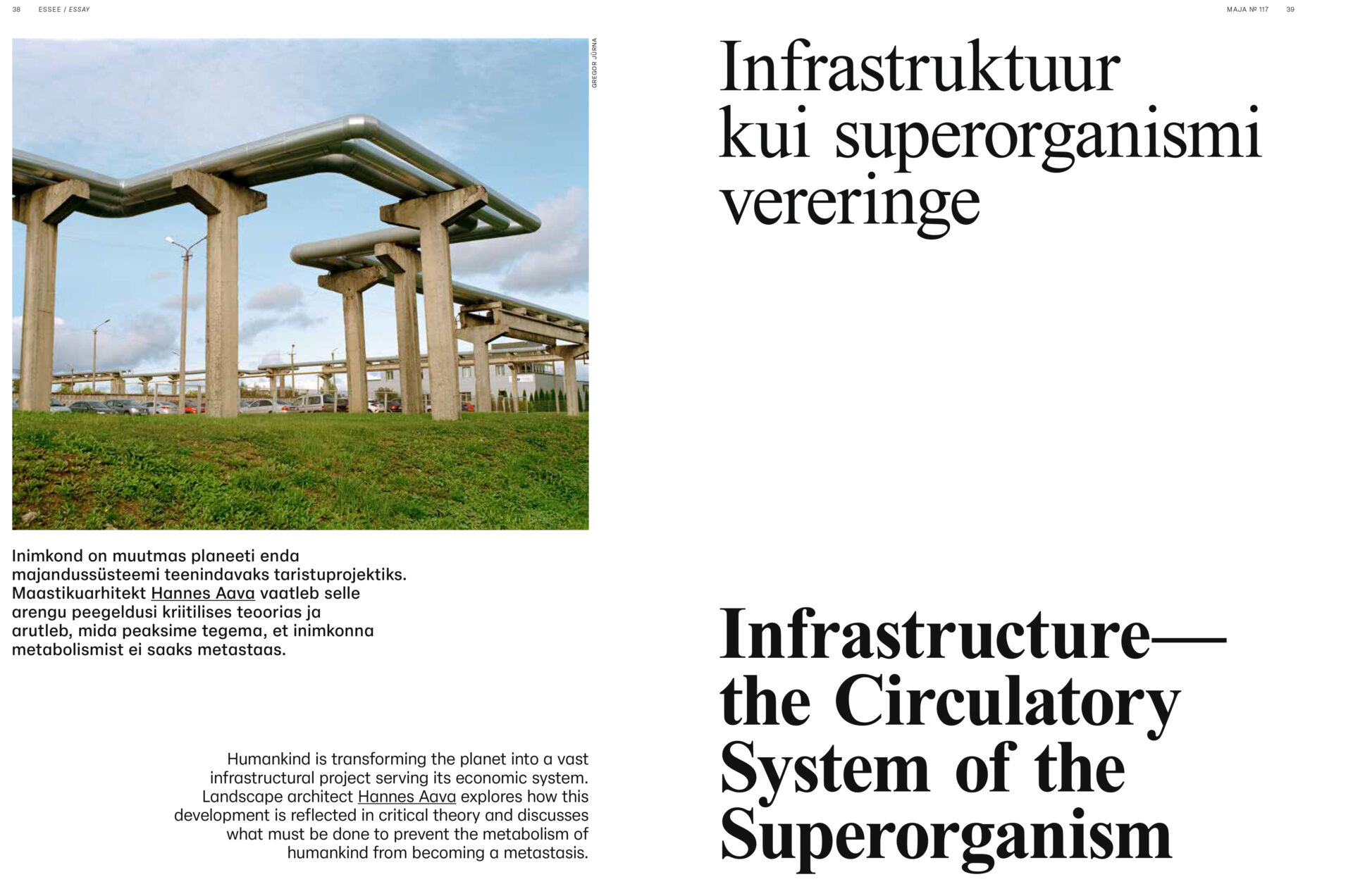

Infrastructure, along with other built environments and structures inserted into natural spaces (such as into the Baltic Sea), forms the circulatory system of humanity’s economic ‘superorganism’, engulfing landscapes both above and below ground. In critical theory, this phenomenon is referred to as a ‘technical land’, encompassing spaces defined by human economic-political systems where the activities of ordinary people and other species are restricted and which often serve a singular, utilitarian function. Peter Galison, one of the early proponents of the term, aptly described it thus: ‘But we see the land, in some irreducible way, as a substrate, as external to us as space and time were to Newton and his followers. History, in this account, is about the use of land – it is borrowed, temporary, and reversible—the way a cast of actors might take over a theatre for a Shakespearian drama one week, and a political party might rent it for a rally the next’.1

The birth and growth of technologically advanced societies have largely depended on the unrestrained and unsustainable exploitation of human and natural resources, in which technical land plays a pivotal role. In Estonia, for example, opposition to phosphorite mining was central to the development of national-political self-awareness in the 1980s. However, the mythical narrative of the so-called ‘forest people’ that emerged in this process seems somewhat dubious in hindsight. It appears that the issue was not so much about preventing the destruction of landscapes, but more about political agency—in other words, about under whose political aegis it would be done, as phosphorite mining is once again on the agenda in Estonia.

In late capitalist discourse, much effort has been made to obscure the social and material costs of one’s actions by transforming spatial issues into kinetic ones through language. For example, ports with infrastructure that devastates coasts, delta wetlands, and river ecosystems while displacing local inhabitants, are described as ‘hotspots’ for capital flows, sustaining a vast machine in the manner of blood vessels. Electric cars are presented as a ‘cleaner’ alternative, yet their increased weight exacerbates the pollution of oceans and rivers, primarily caused by rubber particles from tires. The advancing digital infrastructure has been portrayed in recent decades as an ethereal and free-floating ‘cloud’. This helps to obscure not only its ecological and social footprint but also the labour involved, using abstract concepts to seemingly remove it from the physical reality.

Peter Galison also draws attention to the temporal dimension of technical landscapes and human manipulation of processes that far exceed human timescales. ‘They are intensely local lands, meaning this soil, this evaporation pond, this underground storage tank exist right now. /…/ But technical lands also link us to a past and future through planetary and evolutionary time, leading to spaces that range far more extensively than we reckoned when we built our systems of airports, weapons factories, refineries, plastic production facilities, and toxic legacy sites’. For instance, some nuclear waste from the arms industry has a half-life longer than the age of the human species.

/…/

Full article: https://ajakirimaja.ee/en/infrastructurethe-circulatory-system-of-the-superorganism/

1 Peter Galison, ‘What Are Technical Lands?’, in Technical Lands: A Critical Primer, eds. Jeffrey S. Nesbit and Charles Waldheim (Jovis, 2023), p. 19.