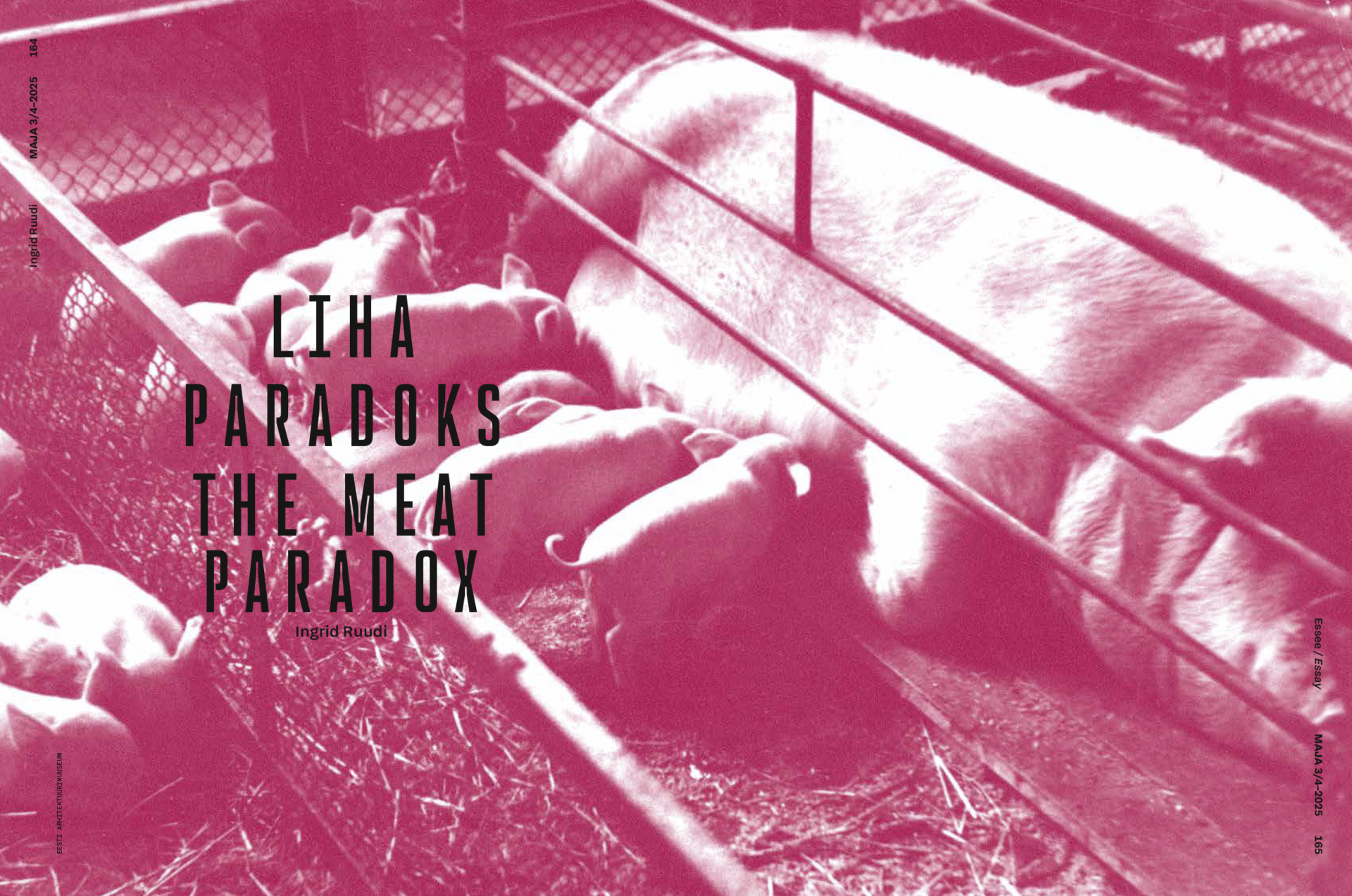

When was the last time you saw a pig? Perhaps you have never even seen one in real life? If so, chances are that you never will—since 2015, letting pigs out of farm buildings is prohibited in Estonia in order to prevent the spread of African swine fever. This means that the animals spend their whole lives indoors—their whole experience of the world is confined to built spaces. Coincidentally, this is a symbolic culmination of a century-and-a-half-long modernist effort to make meat production and the animals involved invisible to humans.

The emergence and development of industrial meat production have played a larger role in the modernisation process than we usually acknowledge. The innovations prompted by considerations of hygiene, cost-efficiency, and effectiveness, combined with changing cultural attitudes towards meat consumption, led to spatial and design solutions that eventually led to the Taylorist conveyor-belt organisation of work. This redefined the modern spaces of labour and consumption, as well as the relationship between the human body and work. Thorough reorganisation of raising farm animals, slaughtering them for food, and the processing, packaging, and distribution of meat began simultaneously in mid-19th-century France and the United States. Although Paris already had five slaughterhouses built outside the city walls in 1818 by order of Napoleon I, the true revolution in the field came with Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s urban transformation project. Between 1863 and 1867, the central La Villette slaughterhouse was built according to his plans. Haussmann himself considered this his most important achievement after the city’s sewage system. Connected to both the port and the railway network, La Villette’s gigantic 56-hectare complex of livestock market and slaughterhouse was meant to house enough animals to supply Paris with a week’s worth of meat and to guarantee clean city streets where butchers no longer slaughtered on site. Thus ended citizens’ complaints about blood running in the gutters, and about disturbing noises and smells, which had been a key issue in the city’s hygiene-related debates alongside prostitution, hospitals, and sewage. However, despite the scale of La Villette, a craft-based attitude and a certain care for the animals persisted—although the spatial setting changed, the practice fundamentally did not. Each animal had its own separate stall, and slaughter took place individually. The complex, featuring neoclassical market halls designed by Victor Baltard, operated successfully for over a century with only minor additions, until it was closed in 1974 and transformed into an urban park based on Bernard Tschumi’s well-known competition proposal.

/…/