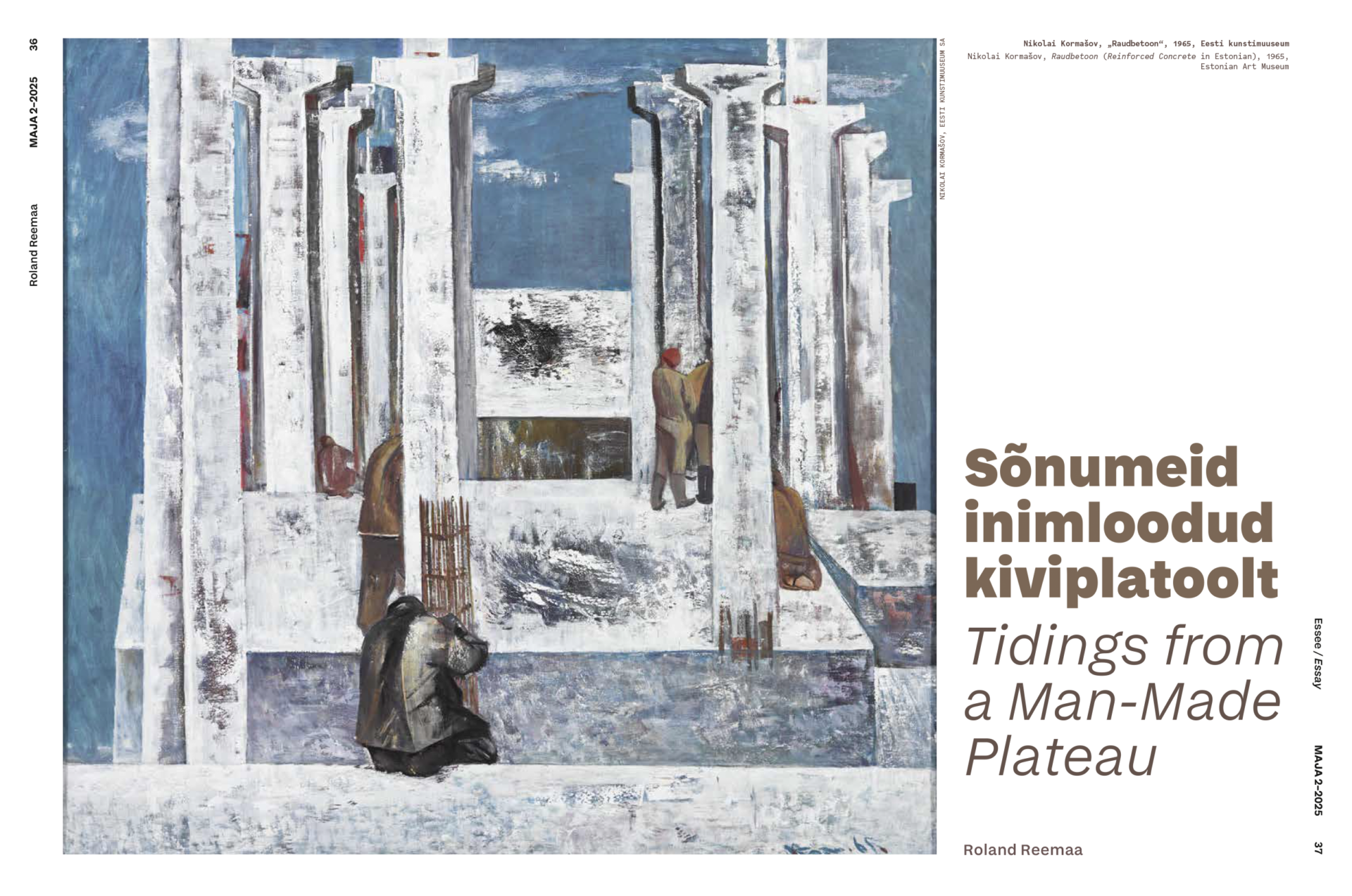

Concrete stuff

Architects and engineers are taken with concrete—a material without a natural form of its own, meaning that it can be shaped precisely to one’s intent, according to physical forces. Its production can be easily repeated, accelerated, globally scaled; its monolithic, uniformly continuous mass resembles man-made stone. In the Estonian language, this has resulted in a deviant categorisation—houses built from aerated concrete blocks are classified as stone buildings, even though such blocks do not occur naturally in the Earth’s crust. Scientists are not unanimous on whether we have already reached the Anthropocene—the geological epoch in which the Earth’s crust is most affected by human activity—but the triumph of concrete sets an example of the planetary impact of our species. Take, for instance, the world’s largest hydro electric power plant, the Three Gorges Dam. The enormous structure holds back 40 billion cubic metres of water, which allegedly slows the Earth’s daily rotation by 0.06 microseconds due to its weight.

Concrete has become synonymous with development. It implies a lot of building and building at scale; it comes with the potential of growing the local economy, creating jobs, improving accessibility, and providing new energy infrastructure. This is what makes the country’s GDP and international competitiveness grow—thus, concrete’s strength is not only physical, but also political. Megaprojects such as dams, highways, data centres, and shopping malls improve the well-being of selected groups of people and soften the impacts of a volatile economy. But are these objects always necessary? Geographer David Harvey refers to such megastructures with the term ‘spatial fixes’. Spatial fixes are objects that result from redirecting surplus capital within a free-market economy into physical space, with the aim of preserving or increasing capital value. Pouring concrete boosts the economy; furthermore, one can always find some spatial issue or other to solve with it. However, Harvey notes that these solutions are unevenly distributed in time and space, and such temporary bursts generate further problems of their own that then need to be addressed. One example of this is our local ‘Euroarchitecture’.1 As Merle Karro-Kalberg pointed out in 2007, no one was really keeping tabs on all the overpasses and concrete sidewalks that were being built. All available funds were simply put to use. Now we have to deal with urban sprawl, car-centric planning, and underground car parks that account for 30–50% of a building’s carbon footprint. Harvey urges us to view concrete not only as a physical body, but in a more abstract way—i.e., not only as a material or an object, but also as a social process.

/…/

1 Merle Karro-Kalberg, ‘Euroarchitecture’, Maja 89–90 (2017)