Toomas Paaver – Architect in the Service of Public Interest

Toomas Paaver has worked as an architect in places where his colleagues have not really wanted to go and with topics that tend to remain in the background: developed national planning at the Ministry of the Interior, worked as a city architect, drawn up competition briefs and study materials, conducted research, familiarised himself with legislative drafting and represented civil associations in numerous planning wranglings. His action has steered spaces that are not born yet – spaces that eventually will be shaped by other architects but their embryonic phase is crafted by terms, agreements and broader spatial concepts of how one or another project could best serve public interests. Since, in Paaver’s opinion, serving public interest is the main aim of spatial planning, ‘I have attempted to get the social consciousness abandon the obsession with the architect as an almighty planner, as there can never be such a thing. Instead, I have tried to suggest a notion that in addition to buildings, architects also work with public space with all the mutual interconnections, set the respective tasks and perceive the spatial connections at large.’[1] He has primarily been a mediator between different parties, an independent meddler, always equipped with relevant arguments – his logical thinking probably stems from his maths studies. As a proactive practitioner, he fits well into the changing role of an architect in the 21st century that tends to see the profession marginalised and transformed into a mere provider of a specific service.

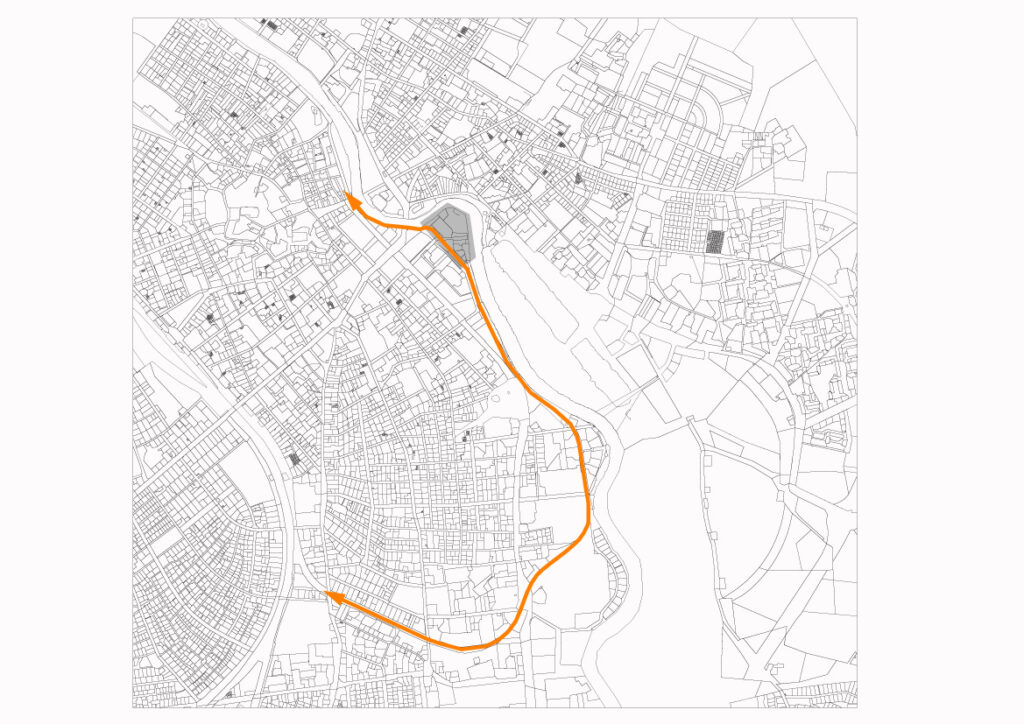

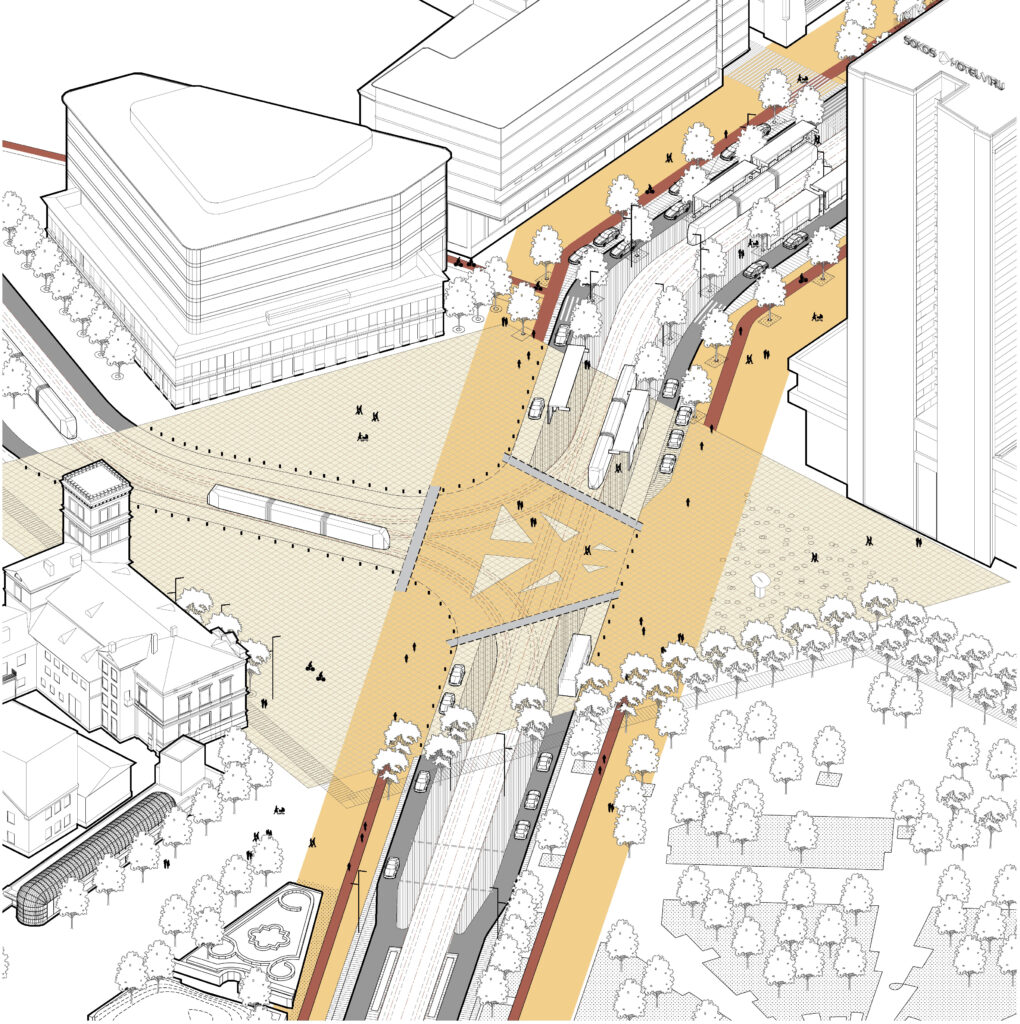

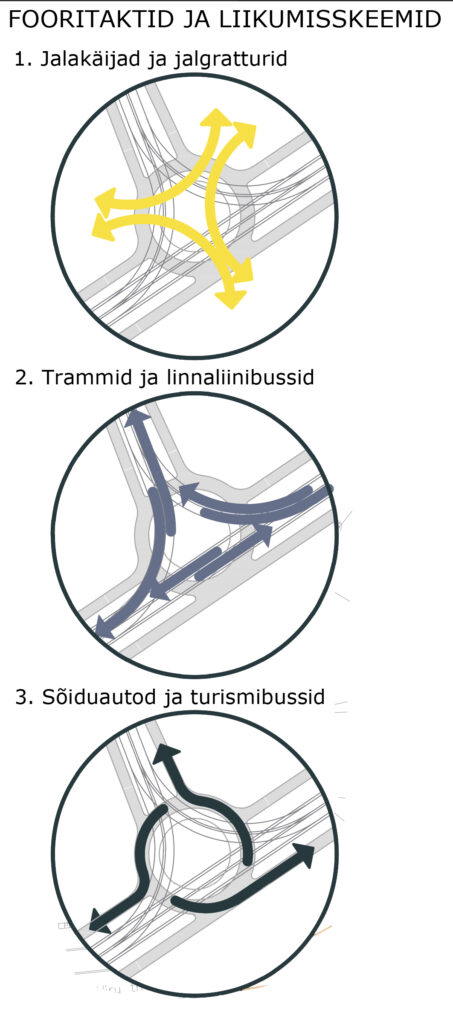

‘At the university, without much external guidance, I came to the realization that street space and the related issues are of utmost importance in the city and architects do not deal with it, although they should. There are plenty of architects who can design high-quality buildings and I did not want to force my way there. I have found other challenges.’ When I ask how an architect develops an interest in legislation, it turns out that while writing his MA thesis, ‘I relied on my imagination in creating a legal structure for how to get public spaces and private property playfully complement one another. I realized that good spatial design relies on the public sector’s statesmanlike understanding of public space as a human network connecting private spaces.’ The so-called civic work took off in the local community association Telliskivi Selts established in 2009 who needed an architect and where he could let his fancy fly. Telliskivi Selts, much like its counterpart in Uue-Maailma district established two years earlier, mark the emergence of the so-called third party in the post-boom reactionary urban design discussion who actually had a real impact on spatial policy – the action to keep Kalaranna open led to a change in the detail plan. According to Paaver, civic work has been very inspiring, ‘I had this strong feeling that we don’t want to be mere protesters, we must be able to provide a vision. It is our task to focus on the person in the street space and on the important public areas, similarly on noticing and mapping the current values.’ Indeed, the best-known completed projects with his contribution have been streets: in Tallinn, Soo Street (technical planning by SKA Inseneribüroo), Vana-Kalamaja Street (author Kavakava) and the Main Street project halted at the moment (with Kavakava), and Roosi Street in Tartu (with Tõnu Laanemäe from Paik Architects and Kino Landscape Architects). By the way, his responsibilities have also included the development of the concepts for the new street design standards, he even renamed it to avoid the continuation of the old approach to traffic engineering.

Traces of his activity are present in various built environments where we may not even suspect it. For example, architects now study in the new building of the Estonian Academy of Arts that is based on the brief drawn up by him in 2014. Or, for about ten years already, the Estonian architecture competition guidelines forming the basis for most of the local architecture competitions have relied on his wording and structure. Partly for health reasons, he has recently been working primarily as a consultant, preferring the completion of projects by means of close communication.

Triin Ojari

[1]Toomas Paaver: An Ambassador of Public Space. Interviewed by Kaja Pae. – MAJA, autumn 2017