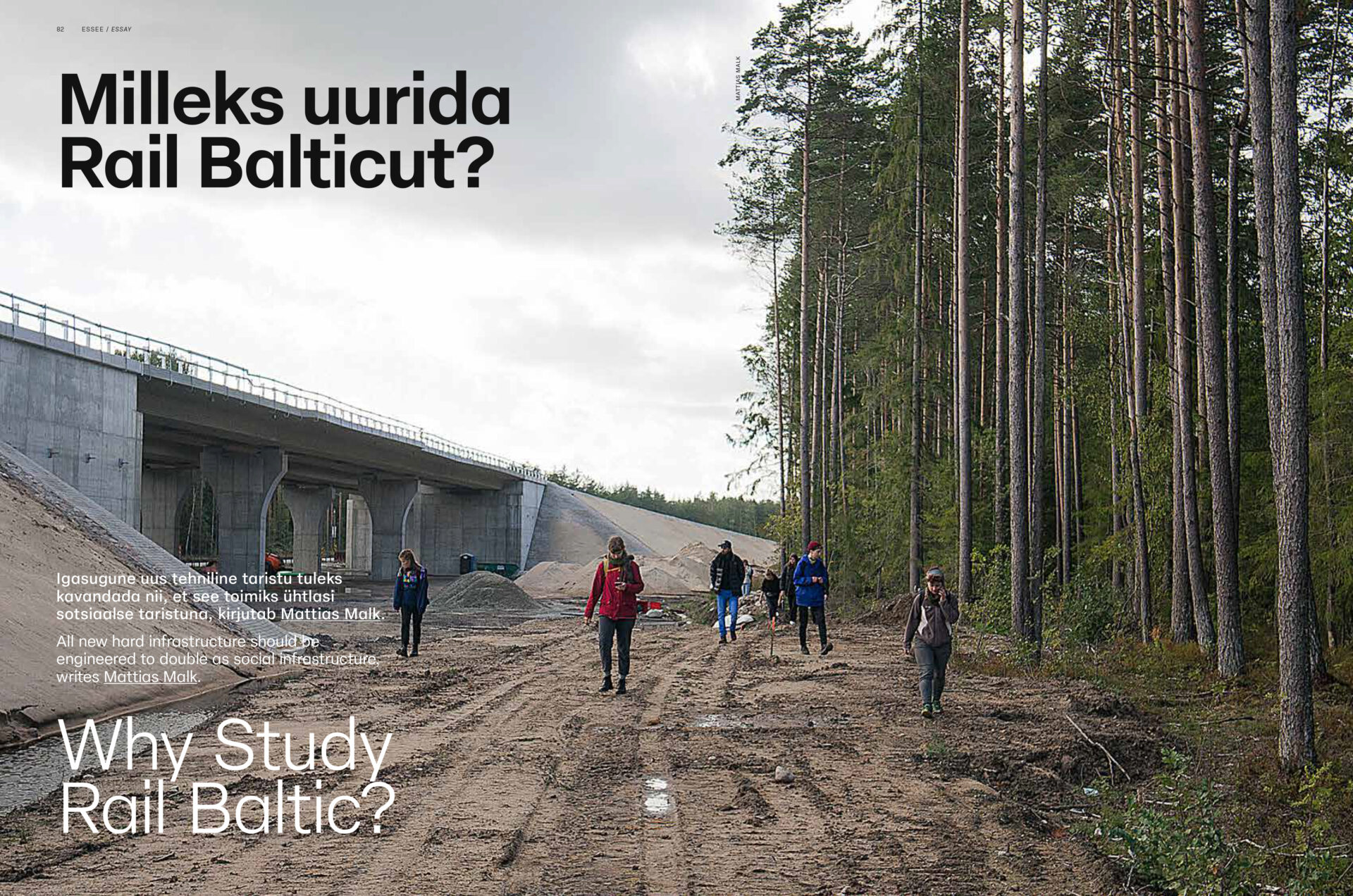

All new hard infrastructure should be engineered to double as social infrastructure, writes Mattias Malk.

Planning and building a railway might seem like a trivial task on the backdrop of a cluster crisis of climate change, war, rising fascism, skyrocketing cost of living, and social injustice, as well as the (mental) health crises associated with each. Even more so if the railway in question is meant to connect small cities in underpopulated countries at the fringes of Europe. Railways, however, have had a significant historical role in establishing the current urbanised spatial order,1 and they continue to be a sustainable option for transportation. Perhaps even more significantly, infrastructure such as railways consists in dense social, material, aesthetic, and political formations that also reflect and undergird societal expectations for the future.

The tendency to overlook the significance of material infrastructure, such as roads, sewers, power lines, pipelines, and railways, can be etymologically traced. The compound of ‘infra’ and ‘struere’, Latin for ‘below’ and ‘to construct’, has led to infrastructure being described as invisible by definition.2 In social sciences, this view persisted well into the so-called mobility turn of the late 2000s and early 2010s that tried to grapple with the increasingly globalising urban world order. Infrastructure came to be considered most visible when it fails, thus abruptly conveying how vital it is for modern urban life.3 The tension between success and failure, between aspiration and stagnation, has made infrastructure a productive topic for social theory.4

As anthropologist Kregg Hetherington details,5 the putative invisibility of infrastructure is not incidental but inherently connected to uneven geographical development. He says that infrastructure has so far been designed to become invisible, and thus provide stability and a platform for processes of a different order—development, civilisation or simply progress.

However, while infrastructure can give assurance about the future and respond to risks, its definitive feature is not invisibility but the narrative of progress. At a time when future is increasingly seen in dark undertones,6 constructing infrastructure is an act of faith that exhibits anticipation for the future. While planners tend to tout megaprojects such as new rail lines as generative locomotives of progress, these narratives often conceal the projects’ (re-)distributive effects at local scale. It needs to be recognised that decisions on what, how, when, and where to connect provide significant opportunities for shaping cities and the lives of citizens. In the context of globalising urbanity, power and wealth are increasingly concentrated in the hands of those doing the connecting or possessing the knowledge to benefit from it.7 Thus, the task for social scientists is to study both the semiotics and materiality of planning to reveal the relationship of risk and ambition inherent in the promise of infrastructure.

/…/

Full article: https://ajakirimaja.ee/en/why-study-rail-baltic/

1 Wolfgang Schievelbusch, The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the Nineteenth Century (University of California Press, 1977).

2 Susan Leigh Star, ‘The Ethnography of Infrastructure’, American Behavioral Scientist 43, no. 3 (1999): pp. 380–82.

3 Stephen Graham, Disrupted Cities: When Infrastructure Fails (Routledge, 2010).

4 Nikhil Anand, Akhil Gupta, and Hannah Appel, The Promise of Infrastructure (Duke University Press, 2018).

5 Kregg Hetherington, ‘Surveying the future perfect: Anthropology, development and the promise of infrastructure’, in Infrastructures and Social Complexity, eds. P. Harvey, C. Jensen, and A.Morita (New York: Routledge, 2016).

6 Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, After the Future (AK Press, 2011).

7 Bent Flyvbjerg, Nils Bruzelius, and Werner Rothengatter, Megaprojects and Risk: An Anatomy of Ambition (Cambridge University Press, 2003).