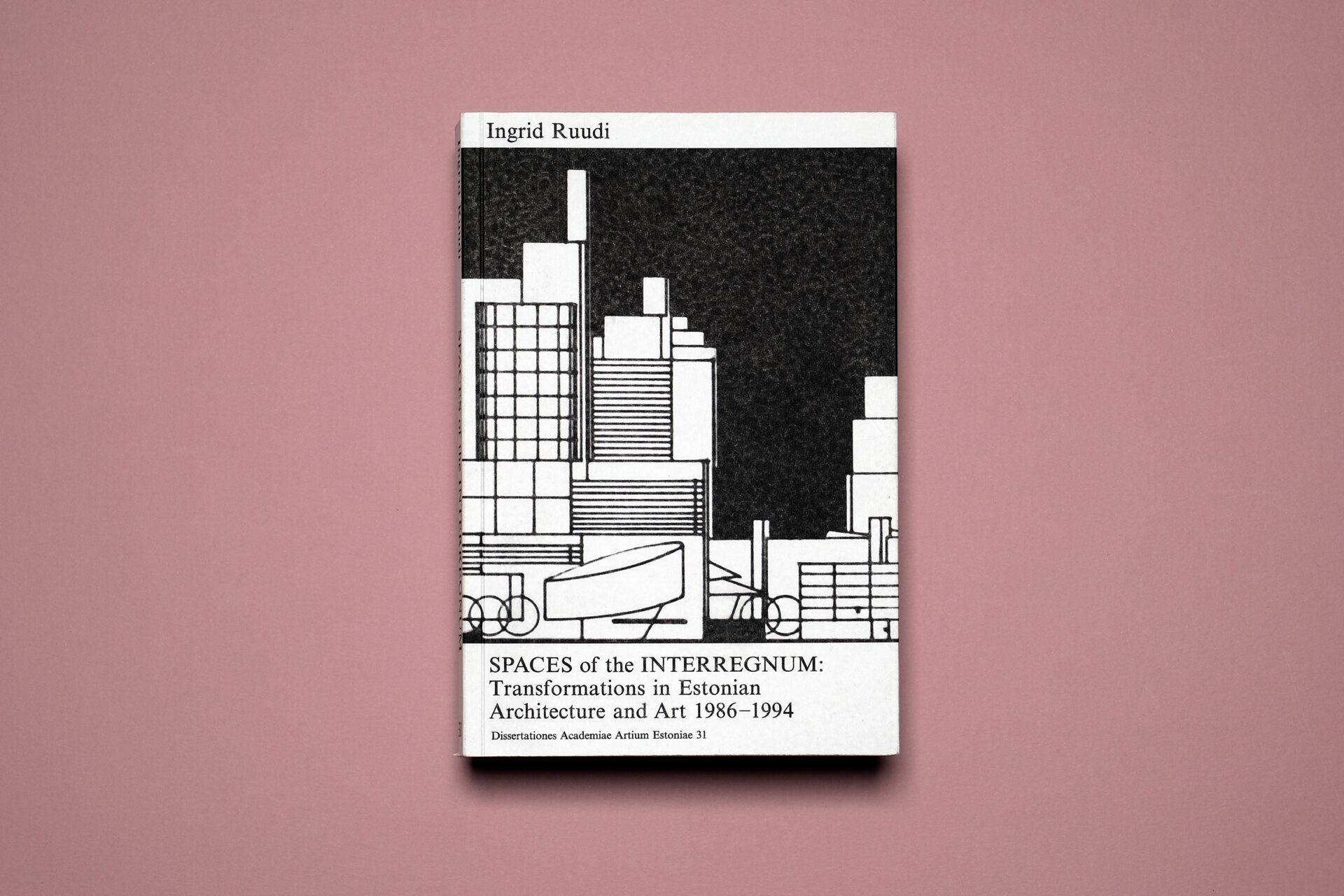

Conventionally, the Estonian architecture history tends to address the late Soviet postmodernism up to the mid-1980s and then resume with buildings of the independent republic from the mid-1990s. The period in between constitutes a kind of gap, and indeed, there was a remarkable decline in building activities. Nevertheless, it was a highly loaded period of active production of new social space, establishment of public sphere and public space, and rethinking of the relationship between built environment and its subject. Those processes continue to have a noted impact on our spatial and social environment up to this day. The doctoral thesis challenges this conventional periodisation of the history of Estonian architecture and art, focusing on the era between two more or less clearly defined social formations – the interregnum of 1986–1994 which must not be treated as a temporary transition on the way to “normalcy” but as a specific period of abundant creativity valuable in its own right. During this dynamic era, certain late Soviet practices continued while accelerated appropriation and interpretation of new western impulses occurred. The transition from one spatial regime to the other did not happen as a clear and definitive cut but rather as a process that was hybrid, fluid and uneven. The dissertation demonstrates how the production of new space took place on various interconnected levels: built and planned, dreamt and imagined, performed and enacted, as well as theorised and reflected.

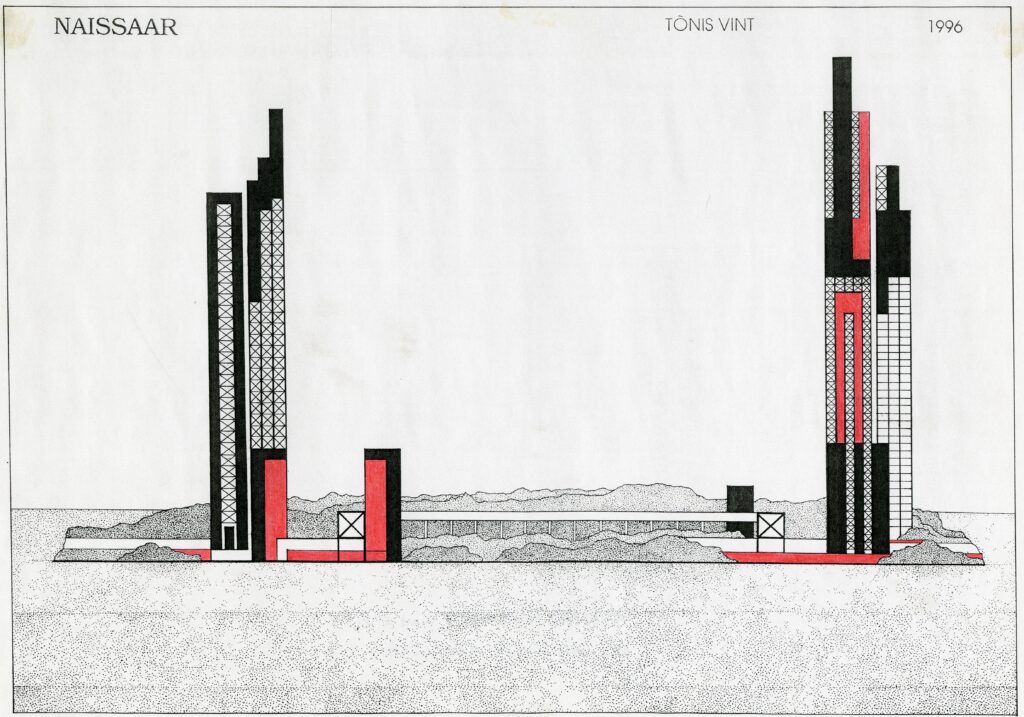

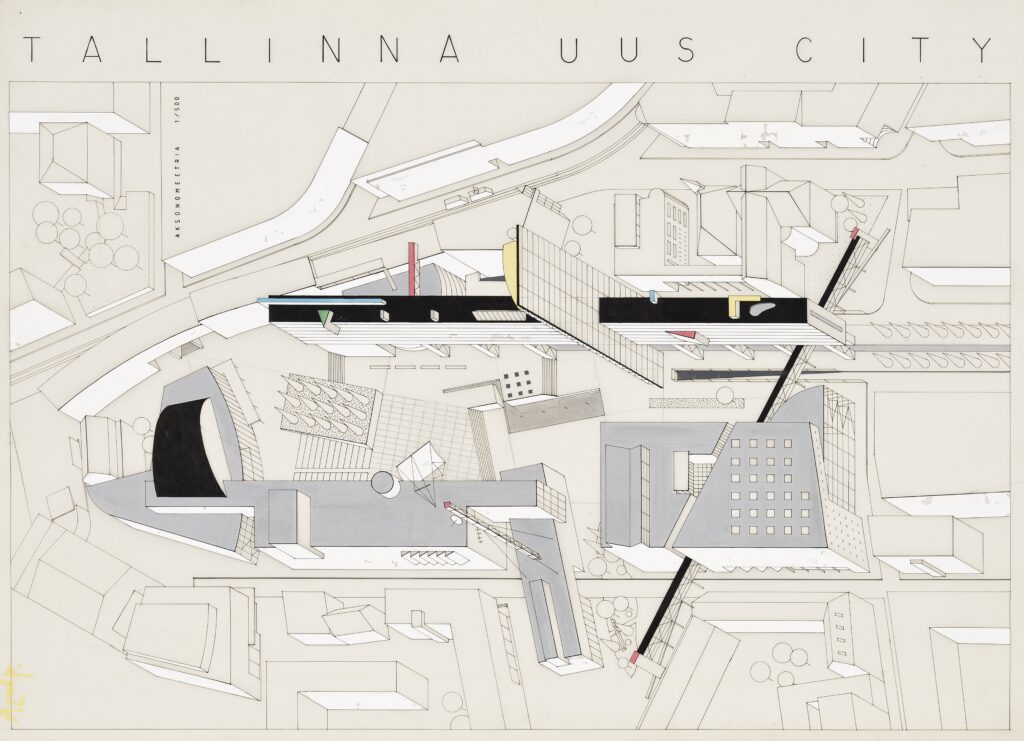

The monographic thesis encompasses five loosely connected case studies. The chapter “Unbuilt space” analyses the most vivid examples of the large number of unrealised architecture projects and urban designs, focusing on aspects such as production of new public space, identity building and the architects’ agency. “Utopian space” looks at artist Tõnis Vint’s vision of a new high-rise urban settlement on Naissaar island near Tallinn, proposed as a free trade zone, considering the case in the context of international economic developments and New Age ideologies. ”Discursive space” focuses on the two first instances of Nordic-Baltic Architecture Triennials as attempts at establishing an international platform for theoretical exchange, demonstrating the different expectations of the Nordic and Baltic participants and diverging positions regarding the issue of regional architecture in the global context. “Performative space” investigates the architecture and performance practices of Group T as an interconnected phenomenon, aiming at establishing temporary counterpublic spaces and an alternative concept of community to counteract the nationalistic social tendencies of the era. “Institutional space” looks at the renovation process of the functionalist Tallinn Art Hall as a conceptual processual work of art by George Steinmann, demonstrating the artist’s agency in establishing international transdisciplinary networks and reconceptualising the art space as a multivalent discursive space. The chapter also addresses the project’s inevitable entanglement with certain neocolonialist allusions and the restitutional mentality of the era, fuelled by the desire for the rebirth of the pre-war republic.

The case studies demonstrate that the Estonian architecture culture from the end of the 1980s to the beginning of the 1990s was far from hibernation: quite the contrary, it was unprecedentedly vigorous and operated in active dialogue with other processes in the production of space for the new society. Making use of the radical openness of the era, the architecture of the interregnum built upon the previous late Soviet experience and realised some of its desires while also testing out new impulses connected with the opening up of the society. The experiments stemmed from belief in creative individuals’ essential role in imagining future space and their right to participate in the public sphere, thus helping to keep the discussions of possibilities open. The spaces thus produced might have been intangible but they were nevertheless vital in shaping the social space of the interregnum and even today.

Ingrid Ruudi