What is your background and how did you end up in architecture?

When studying philosophy at the Institute of Humanities, we focused on continental philosophy which tends to emphasise creativity and the searching spirit. But in the academia, it has been overshadowed by the analytical and logic-based approach. The latter, unfortunately, does not yield any people who could think together with architects. I came to the Academy of Arts quite by chance in 2008 – they had been looking for a lecturer for some time already. At about the same time, the Dean of the Faculty of Architecture Toomas Tammis asked me to lead a philosophy reading group. Because of this, I was later asked to supervise the written parts of architecture students’ Master’s theses. At first, I didn’t understand anything about architecture but I gradually started to grasp the terminology and understand how they think about and teach the process of creating spaces.

Could we call you a translator? Your texts aim at explaining certain conceptual tangles.

I guess so. Then again, in the first years I didn’t say a single word about architecture, I was merely taking it all in. This changed in 2011, when a discussion between Anti Saar and I was published in the issue of Ehituskunst (2011) edited by Martin Melioranski. In this conversation, I formulated the concept of the incomplete spaces that is still of great significance to me.

In 2013, you cooperated for the first time with architects in competitions – the church in Mustamäe with Kavakava and the cenotaph for heads of state in Metsakalmistu cemetery with Kuu. And then in four years, five more competitions with the latter.

I was in the editorial board of Ehituskunst when Indrek Peil stated in one of the meetings that theory is nice indeed, but actually architects tend to etch and scribble when discussing things with each other. I found this an interesting research topic and the editors of Ehituskunst Kadri Klementi and Aet Ader suggested that I write an article about it. They would get me into some architecture offices to join a competition project. Kuu was one of them and we hit it off immediately. So we did the cenotaph for heads of state and we won. This was followed by several other projects. Among other things, we participated in Tallinn Architecture Biennale with Kuu and Siiri Vallner in the same autumn. Later I also did several competition projects with Kadarik Tüür Architects but now there is a longer break until I complete my doctoral thesis.

What surprised you the most about the work taking place behind the scenes? What is different?

The collective nature of the work, the briefs are very straightforward – a particular plot, considerable restrictions on everything – and so you need to navigate between the limitations. At first, I wasn’t sensitive to space at all, I didn’t notice many relevant things. So the process was like this – we went to the site with Kuu architects and they just told me what they saw and felt. I could react to their ideas with my observations and associations. If the written explanations for the competition entry are usually written in haste at the last minute, then in our projects I often wrote a temporary version in the middle of the project. This allowed us to organise our thoughts and provided us with the images that could be later expressed in space. The text provided the scaffolding. At times I feel that I mainly contribute not as a philosopher but as a poet, finding the appropriate poetic images for the project, which are half-verbal and half-spatial. If my background in philosophy has helped me in anything, it’s that it allows me to quickly get into the conceptwares of different fields and question some of the more fossilised aspects.

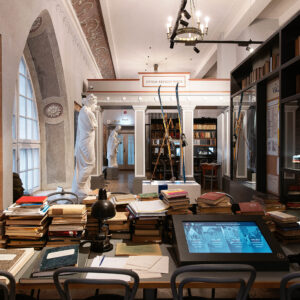

One of the most important works you did with Kuu is the new building of the Estonian Academy of Arts. How did this transpire?

We based it on the concept of an incomplete space, as it seemed appropriate here. We had fierce discussions about many things: which historical layers should be retained (the brief demanded a smaller building than the existing factory premises), if the courtyard should be raised, where exactly should we make the cut etc. We agreed that we would value all historical layers and retain as much as possible. I had discussed the qualities and importance of raw drafts also in my philosophy lectures. I was strongly of the opinion that the unbuilt academy building in Tartu Road was too finished, too pretty, too much of an object. Also the current academy building could have been much cruder. It’s a question of control – when is your work done? For instance, at the academy I still see that people are too much in awe of the space, nobody has taken up a brush to repaint some parts. Perhaps the space looks too ready?

Then again, each cooperation has been very different. In the more successful cooperations, laughter has played a considerable role. For instance, the exhibit we did with Molumba for the exhibition “Houses that we Need” at the Museum of Architecture was born out of laughter, although the topic itself was serious. We used jokes to express our deep frustration about the ways the new green regulations are thought about by the city governments and clients – it’s all highly superficial.

Cooperation with architects has considerably heightened my sensitivity to spatial problems. You’d think that architecture is the most conformist of the arts (and in some respects it has to be) but my experience offers many examples to the contrary.

There was another visible project you did with Mihkel Tüür and Rene Valner – “Nearly Zero” (2018) – addressing the topic of energy crisis and the need to drastically lower our carbon footprint, which hasn’t lost its relevance to this day.

The initial idea was to be highly ironic. The starting point was that all buildings would be getting exceptionally ugly, the rules would be useless and just result in endless bureaucratic misery. Architects know that creative work constitutes only a tiny segment of the principal building design documentation with hefty paperwork forming the rest. They are now increasingly more concerned with bookkeeping. The idea to use oil barrels for displaying the information came from bouncing ideas around with the graphic designer Uku-Kristjan Küttis. It took some time to get me convinced of its appropriateness. As there was no time for exquisite design, I simply wrote a headline and a sentence for each barrel and Mihkel drew the accompanying pictures. The exhibition perhaps accomplished its purpose of making people aware of the issue. It certainly spoke to young people. I actually wrote an e-mail to all schools in Tallinn that they should come and see it. We are also planning to establish a competence centre about these issues. I would never have thought about making such an exhibition myself: it was Mihkel who initiated it. The same is true for most of my architectural projects – the initiative usually comes from the architects.

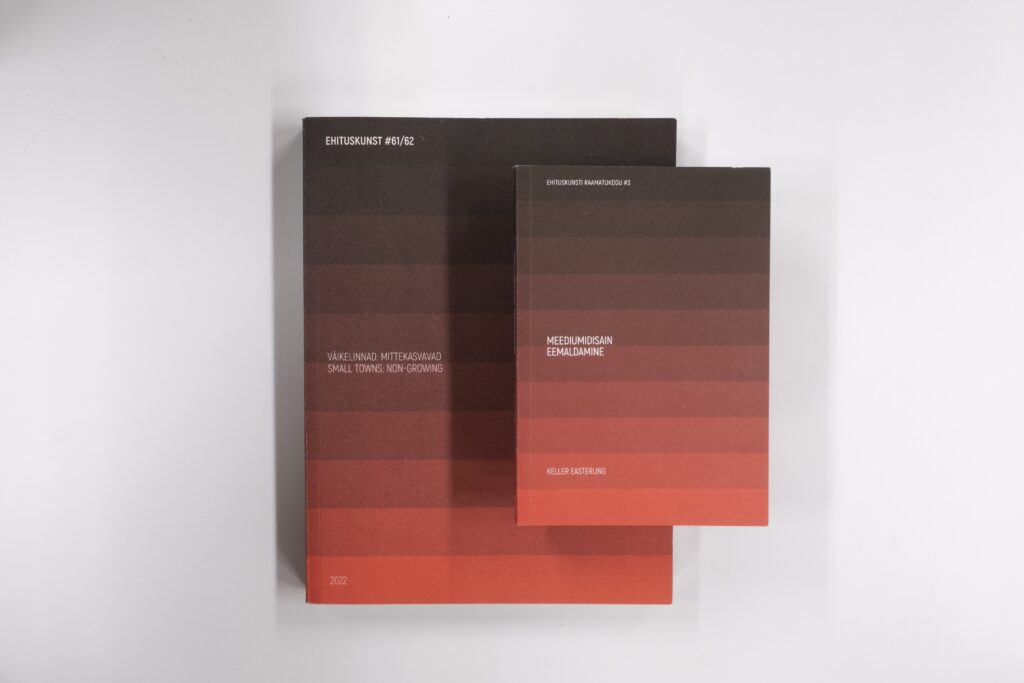

You have edited two issues of Ehituskunst. What’s the situation with topics there?

There I certainly have a stronger “authorial position”. I did not want the review to be only theoretical as it had been for a while. It seemed that nobody read it – I’m not sure if anybody reads it now either. Still, I wanted to go back to its roots and bring back the practical side that had been there in 1980s, when the magazine started. My idea was to have a mix of practical and speculative ideas that would together correspond to this idea I had about the deep architectural research. I also wanted it to have a feel of a raw draft, in order to protest against the more glossy look of the usual design magazines. I didn’t quite achieve that – just like with the academy building, the glamour and glossiness secretly crept in from the other participants of the design. On the one hand, I have considered Ehituskunst as a platform that could help to find some real solutions while also suggesting ideas for paper architecture – the kind of architecture that is not necessarily meant to be realised, but has a more explorative spirit. Estonia tends to be quite a pragmatic place where everybody is so preoccupied with everyday business that there is not much time for dreaming.

Let’s take a step further here – the key questions of contemporary architecture. How will architecture cope in the world of climate crisis, energy efficiency and overall sustainability? On the one hand, we shouldn’t build anything anymore, then again, we annually award prizes to buildings that have taken a mound of concrete and other materials. Has the new generation already uttered the question when it will be enough?

First of all, architecture does not have much power. Architects are severely delimited by more powerful parties, for example, developers. In my opinion, architects should start developing themselves, even if only a little. I’ve witnessed too many times how architects have had futile discussions with developers and how tremendous spatial potential is constantly wasted. There are already many examples in the western world of architects doing the developing, so there’s even no need to reinvent the wheel. Perhaps it’s time to establish an inter-office development company? This is the only way for architects to have a proper choice and to have a say in urban design solutions, the use of higher-quality and planet-friendly materials etc. The other option is to do it via regulations, this should also be pursued. I don’t think that construction is a crime, but we should take more time to think and calculate before we start taking action. In his interview for the latest Ehituskunst, Siim Raie said that in Estonia we play a zero-sum-game – every larger new-build means a death sentence for some existing ones. All this could be computed and respective requirements set by regulations: the costs of the older buildings left over due to new-builds. Then again, Alvin Järving has said that if the existing building cannot indeed be used, let’s at least make the new one last for 300 years.

One of the most critical points here is residential construction – our legacy includes a large amount of inappropriate housing, and also today, the new residential units comply with the market rules but do not meet our real expectations.

We have little affordable housing and what we have is of particularly low quality. Very little attention is paid to bringing the good and the affordable together. So far, no co-building and co-developing models have been used in Estonia. Also, the market has no desire to deal with reconstruction projects as it is not profitable. For instance, students have suggested thoroughly feasible improvement ideas for Mustamäe, but nobody seems to be interested in implementing them. All these aspects also argue for architects taking up development themselves.

In these projects I often feel like I don’t have necessary tools to be really helpful. I have taken Ehituskunst as a kind of preparatory explorative work to develop these kinds of tools. Hopefully, it has a similar function also for others. In architecture, the preliminary work cannot be academic only – it must be much bolder and more speculative. It’s a tentative translation towards the future.

In her book “Medium Design” that I translated (Eesti Kunstiakadeemia Kirjastus, 2022), Keller Easterling says that in case of good built environment, the most important impact may be indirect. For example, if somebody could come up with a new affordable and well-designed typology for residential houses in Tallinn, or if in cooperation with banks and developers we could come up with new financial instruments and possibilities for developing residential areas that are better attuned to our future needs, then it would have a considerably stronger impact than some single fancy project. The health of architecture depends on the conditions in which it operates. In the right conditions, our architects are entirely capable of making excellent architecture.