Ingrid Ruudi discusses architects’ relationship with time and the various ways in which architects in their later years record their doings as history.

Architects have a very specific relationship with time. A keen eye for the present is an obvious prerequisite, but designing and imagining new spaces actually requires mentally projecting oneself in the future. At the same time, there should—ideally—be an equally good understanding of the past—of how time and circumstances have shaped the kinds of spaces that we currently have. The need to operate simultaneously in different temporalities can even feel slightly schizophrenic. What is, in fact, a work of architecture, and when? Right now, when it exists only as a design? In the future, when it will be built? Even further in the future, when it would become inhabited? Let us not even speak of the megalomaniacs who considered architecture in the perspective of a thousand years, including its eventual state of ruins. If we add to this the inevitable slowness of architectural production—a number of time-consuming circumstances that do not depend on the architect and can sometimes even halt the process for months or years—then it is no wonder that an essential part of the profession is a need and effort to gain control of time. Just as designing requires a certain bird’s-eye view of the future, architects are also keen to take care, and take control, of how their work is recorded in history.

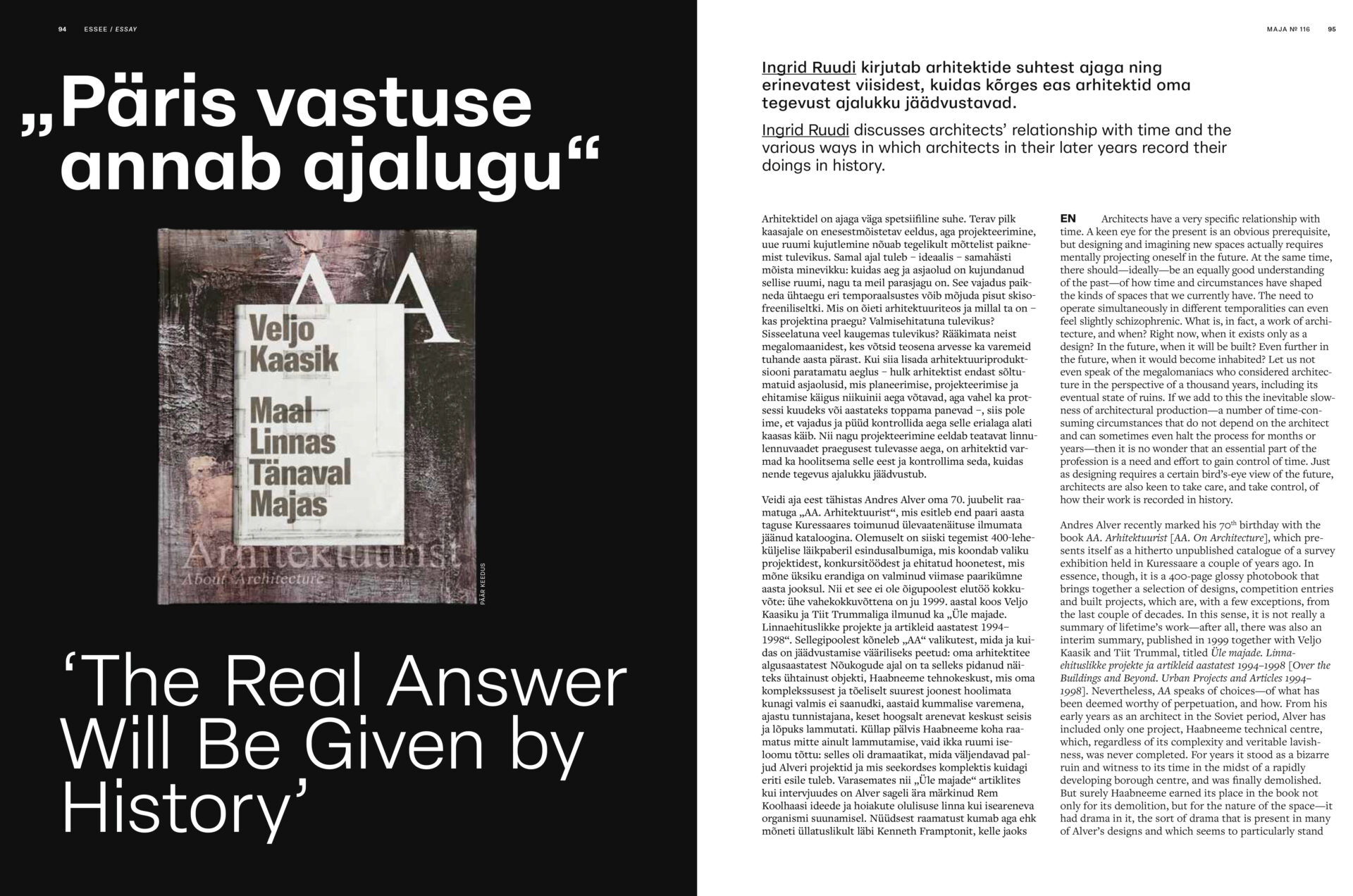

Andres Alver recently marked his 70th birthday with the book AA. Arhitektuurist [AA. On Architecture], which presents itself as a hitherto unpublished catalogue of a survey exhibition held in Kuressaare a couple of years ago. In essence, though, it is a 400-page glossy photobook that brings together a selection of designs, competition entries and built projects, which are, with a few exceptions, from the last couple of decades. In this sense, it is not really a summary of lifetime’s work—after all, there was also an interim summary, published in 1999 together with Veljo Kaasik and Tiit Trummal, titled Üle majade. Linnaehituslikke projekte ja artikleid aastatest 1994–1998 [Over the Buildings and Beyond. Urban Projects and Articles 1994–1998]. Nevertheless, AA speaks of choices—of what has been deemed worthy of perpetuation, and how. From his early years as an architect in the Soviet period, he has included only one object, Haabneeme technical centre, which, regardless of its complexity and veritable lavishness, was never completed. For years it stood as a bizarre ruin and witness to its time in the midst of a rapidly developing borough centre, and was finally demolished. But surely Haabneeme earned its place in the book not only for its demolition, but for the nature of the space—it had drama in it, the sort of drama that is present in many of Alver’s designs and which seems to particularly stand out in this publication. In his earlier articles, like those included in Over the Buildings and Beyond, and earlier interviews, Alver has often mentioned the importance Rem Koolhaas’s ideas and attitudes for his understanding of steering urban developments. The present book, however, somewhat surprisingly also echoes Kenneth Frampton, for whom one of the core values was city as a space for public appearance. Alver emphasises that in addition to rationality, cities also need to feature ‘something more’; people oversaturated with virtuality also need real physical experiences, not just random ones but encounters of consciously designed space. In the book, the architect comes across as a great dreamer (the texts that explain competition entries and unrealised designs are particularly rich in sentences that end with the ellipsis) whose mission is to orchestrate the big picture. ‘A comprehensive composition is something to pursue,’ he writes, and surely this is not an empty formal composition, but a spatial setting full of polyphonic activity. In such a vision, the urban space appears as outright symphonic, the city as one big spectacle.

It is clear that Alver wants to go down in history as a Creator. Instead of narrating his own memoirs or the story of his development, he is opinionated about the contemporary practice of architecture competitions as well as the whole of 20th century; in this sense, the texts speak to us from the perspective of someone who is still engaged in action rather than summing up and looking back. Indeed, architecture is one of the few fields that has not yet been overcome by the cult of youth, but where authority accumulates over time, and ageism does not rule out one’s best works being born late in one’s career. The driving force for the author has been unceasing dissatisfaction—at times, the author states his scapegoats openly; other times, they are left more ambiguous. There seems to be an underlying suspicion that perhaps our city dwellers do not even deserve all that beauty of urban life. The people of the forest do not know how to live in a city—Alver is not the only Estonian architect who has come to this bitter conclusion, but perhaps one of the most stubborn and impatient ones. And although a book as ambitious as this surely aspires for wider publicity, both the visuals and the text make it clear that the author is primarily addressing his own professional community—those who know and understand. ‘The real answer will be given by history,’ states Alver when writing about competitions—after all, in assessing their journey and their works, architects do not look to the present day, but rather the macro-scale of time. Architecture is a Sisyphean task, but nevertheless an infinitely optimistic one—sometime in the future, the historical perspective would finally reveal the correct answer, and the good and right solution would prevail.

/…/

Full article: https://ajakirimaja.ee/en/the-real-answer-will-be-given-by-history/